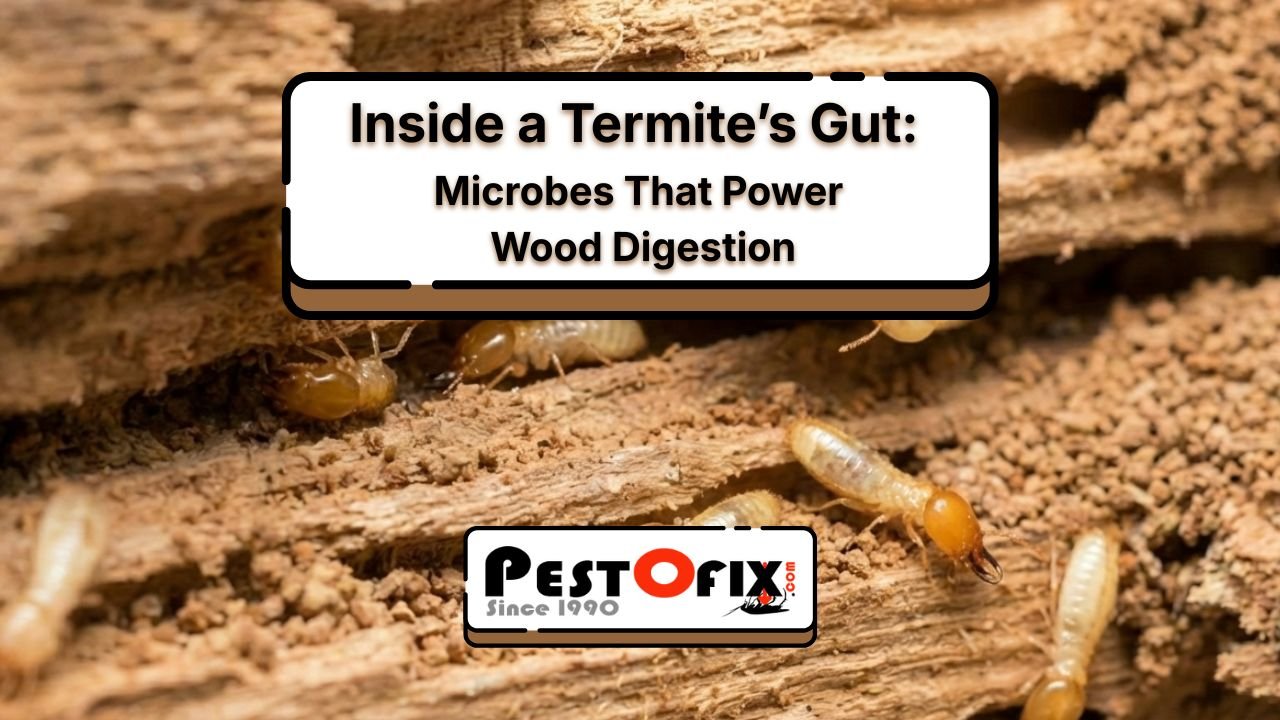

Inside a Termite’s Gut: Microbes That Power Wood Digestion

Introduction

Termites are often described as silent destroyers, capable of consuming massive amounts of wood while remaining almost invisible. Yet, what makes termites truly extraordinary is not their jaws or appetite — but what happens deep inside their bodies. Termites cannot digest wood on their own. Instead, they rely on a complex internal ecosystem of microbes that perform one of nature’s most remarkable biological processes.

Inside a termite’s gut exists a microscopic world of bacteria, protozoa, and archaea working together in perfect coordination. This hidden community breaks down tough plant fibers that most animals cannot digest, converting wood into usable energy. This article explores the science behind termite digestion, the microbes that power it, and why this symbiotic relationship is one of evolution’s greatest successes.

Why Wood Is So Difficult to Digest

Wood is primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin — materials designed by plants to provide strength and resistance against decay. Cellulose molecules form tightly packed chains that are extremely difficult to break apart. Lignin, in particular, acts as a protective barrier, shielding cellulose from microbial attack.

Most animals lack the enzymes required to break cellulose into usable sugars. Even herbivores like cows rely on gut microbes for digestion. Termites take this dependency to an extreme, outsourcing nearly all wood digestion to their internal microbial partners.

- Cellulose: A complex carbohydrate forming the structural framework of plants.

- Hemicellulose: A supportive compound binding cellulose fibers together.

- Lignin: A rigid polymer that protects plant cell walls from decay.

The Termite Digestive System: Built for Symbiosis

The termite digestive tract is not a simple tube. It is a highly specialized, multi-chambered system designed to house and support microbial life. Each section of the gut creates unique conditions — oxygen levels, acidity, and nutrient availability — tailored to different microbial species.

- Foregut: Mechanically grinds wood into smaller particles.

- Midgut: Absorbs simple nutrients and prepares material for fermentation.

- Hindgut: The microbial fermentation chamber where cellulose digestion occurs.

The hindgut is the true engine of digestion — an oxygen-free environment packed with billions of microorganisms working in cooperation.

The Microbial Community Inside a Termite’s Gut

The termite hindgut hosts one of the densest microbial ecosystems found in nature. A single termite can carry thousands of microbial species, each performing a specific role. These organisms form a tightly linked food web where waste from one species becomes fuel for another.

- Protozoa: Primary cellulose digesters that break wood fibers into sugars.

- Bacteria: Convert sugars into short-chain fatty acids and nutrients.

- Archaea: Consume hydrogen and produce methane, maintaining gut balance.

This collaboration allows termites to extract energy from materials that would otherwise pass through undigested.

Protozoa: The Primary Wood Digesters

Protozoa are the most critical players in termite digestion. These single-celled organisms possess specialized enzymes called cellulases, which break cellulose into glucose molecules. Some protozoa even contain bacteria inside their own cells, creating multiple layers of symbiosis.

- Flagellated Protozoa: Use whip-like structures to move and stir gut contents.

- Cellulose Breakdown: Convert plant fibers into simple sugars.

- Internal Symbionts: Host bacteria that assist in fermentation.

Without protozoa, termites would starve — a fact proven by experiments where removing gut protozoa leads to termite death.

Bacteria: The Chemical Engineers

Bacteria inside the termite gut perform an astonishing range of chemical transformations. After protozoa break cellulose into sugars, bacteria ferment those sugars into short-chain fatty acids like acetate — the termite’s primary energy source.

- Acetogenic Bacteria: Convert hydrogen and carbon dioxide into acetate.

- Fermenting Bacteria: Break down sugars into usable compounds.

- Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria: Supply essential nitrogen nutrients missing from wood.

This process ensures termites obtain not only energy but also vital nutrients from an otherwise nutrient-poor diet.

Archaea: The Balance Keepers

Archaea are ancient microorganisms distinct from bacteria. In termite guts, they play a crucial role in regulating hydrogen levels produced during fermentation. Excess hydrogen can halt digestion, so archaea consume it, maintaining chemical stability.

- Methanogens: Convert hydrogen into methane.

- Energy Regulation: Prevent fermentation from stalling.

- Gas Production: Responsible for methane emissions from termites.

This delicate balance keeps the entire digestive system functioning smoothly.

Symbiosis: A Perfect Biological Partnership

The relationship between termites and their gut microbes is a textbook example of mutualism. Termites provide shelter, moisture, and food. Microbes provide digestion, nutrients, and survival.

- Microbes Gain: Safe habitat and constant food supply.

- Termites Gain: Energy, nitrogen, and survival capability.

- Colony Benefit: Efficient food sharing through trophallaxis.

This partnership has evolved over millions of years and is passed from one generation to the next.

How Termites Inherit Their Microbes

Termites are not born with gut microbes. Instead, they acquire them through social interaction. Young termites receive microbes by feeding on fecal matter or saliva from older colony members — a process known as trophallaxis.

- Microbial Transfer: Passed through feeding interactions.

- Colony Dependency: Isolated termites cannot survive long.

- Social Bond: Reinforces colony cohesion.

This method ensures microbial continuity across generations.

Evolution of Termite Digestion

Termites evolved from wood-feeding cockroach ancestors. Over time, their digestive systems became more specialized, and their dependence on microbes increased. Some termite species evolved complex gut compartments resembling miniature bioreactors.

- Primitive Termites: Heavy reliance on protozoa.

- Advanced Termites: Increased bacterial specialization.

- Fungus-Growing Termites: Outsource digestion to cultivated fungi.

Fungus-Growing Termites: External Digestion

Some termite species take digestion a step further by farming fungi. They deposit wood in special chambers where fungi break it down before consumption. This is one of the most advanced examples of agriculture in the animal kingdom.

- Fungus Gardens: Pre-digest wood externally.

- Nutrient Enhancement: Improves food quality.

- Colony Efficiency: Reduces internal digestive load.

Why This Matters Beyond Termites

The termite gut microbiome has attracted scientific interest worldwide. Researchers study it for applications in biofuel production, waste recycling, and sustainable material breakdown.

- Biofuel Research: Cellulose-to-ethanol conversion inspiration.

- Waste Management: Natural decomposition models.

- Microbial Ecology: Understanding complex symbiotic systems.

Conclusion

Inside a termite’s gut exists a living ecosystem more complex than many forests or oceans. This microscopic world powers one of nature’s most efficient recycling systems, transforming wood into life-sustaining energy through cooperation and balance.

Termites do not conquer wood through strength alone — they succeed through partnership. Their survival is proof that intelligence in nature is not always found in brains, but in relationships perfected over millions of years of evolution.

No comments yet — be the first!